By Michael Allen, Free Press Staff Writer | Friday, June 23, 1989

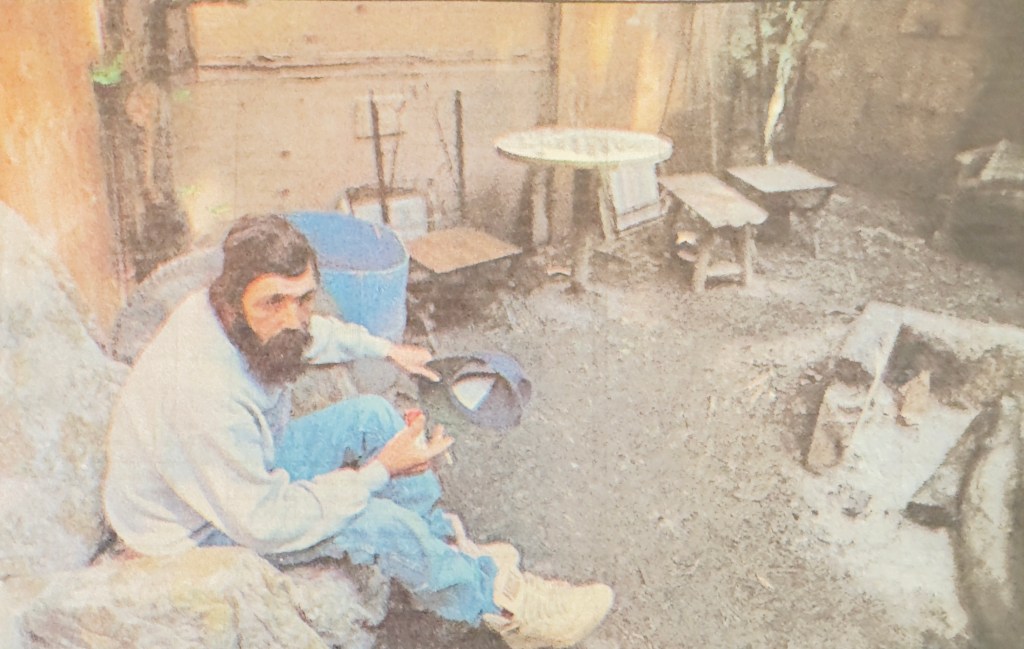

Framed by giant ash and poplar trees, the hobo encampment along the banks of the Winooski River was a special place for Dennis Racine.

In 1983 he and Joe Martin had built the encampment, a sheltered area filled with armchairs, mattresses, cupboards, bookcases, a clothesline, a toilet, a file cabinet and a plastic drum – things the men dragged there over the years.

Racine died three weeks ago in a favored armchair in the encampment, and Martin mourned his loss at the camp as the sky grew dark, the mosquitoes grew fiercer and a tree limb burned in a fire nearby.

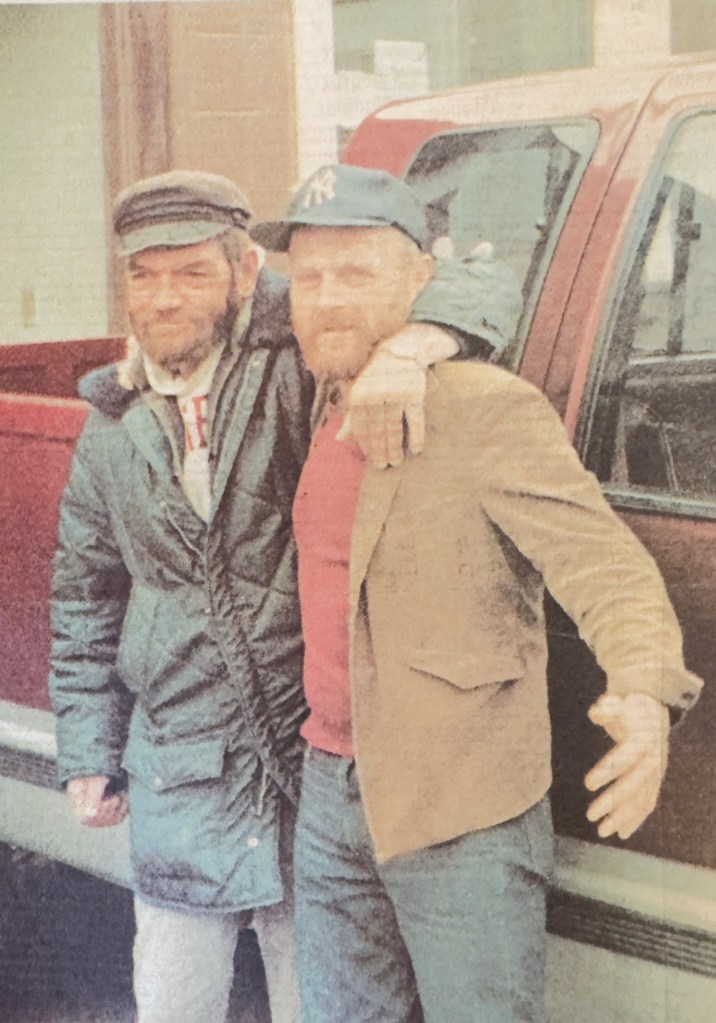

“I’ll tell you how Dennis lived. Dennis was my best buddy – my partner for 30 years,” said Joe Martin, who first met Racine when the two were teenagers in Burlington. “We drank together.”

“I never thought in my born days that Dennis will die in a chair without me. I’m the one with the bad lungs,” Martin said, pointing to an armchair covered with a sheet.

“What they said was, he curled up and died of his own phlegm. I expect that to happen to me because I’m a cougher and a hacker. But, Denny …” He shook his head in disbelief.

Racine spent 25 years as a street person – becoming a fixture on North Street in Burlington’s Old North End. His friends said he went to the street to die.

“When I die, I want to die alone; by the river,” his friends recalled him telling them time and again. “I don’t want no tears; I don’t want no flowers.”

When his final hour came the evening of June 1, Racine, 29 days short of his 44th birthday, went to the encampment by the river, got into his favored armchair and died.

He was the best known of the three transients who died between May 30 and June 1, officials said. Police have ruled the deaths of Oinus Jones and Keith Destrom, who died that same week, were homicides.

But Racine died of natural causes, a victim, perhaps, of years of heavy drinking and living on the streets. Dr. Eleanor McQuillen, chief state medical examiner, said he was in a position in the chair that pressured his chest cavity, stopping his breathing. Blood tests to see if alcohol contributed to his death are pending.

The street people who were Racine’s closest friends were not allowed to view his body before it was cremated. They were not allowed to pay their respects.

“When we went to see Denny, Denny was laid out in a beautiful black suit, a white shirt, a black tie. He had flowers, which he always said he never wanted. … He had a good casket,” said Shirley Boucher, a North Street resident who met Racine 25 year ago and remained friends with him until his death. The family permitted Boucher to pay her respects.

“I can tell you why it was a private funeral. It makes sense,” Boucher, 55, said. “Denny was street people. OK, from every walk of life: rich, poor, clean, dirty, drunk or sober, young, old. Dennv’s family did not live like this. So, when he died, there is no way they wanted all of these people that Denny knew coming in and out of the funeral parlor.”

The street people saw it another way. Racine was family. A June 16th vigil on the steps of Burlington City Hall provided them their only opportunity to mark his passing.

“We are more Denny’s family than them,” said Bill Provost, a 32-year-old street person. “They come down here and they don’t want anything to do with us kind of people. That’s wrong.”

Roger Senna, another Racine acquaintance, declined to discuss Racine’s death, as did Racine’s brother, Conrad Racine of Westford.

“All you guys want to do is sell papers. Why don’t you just leave him alone? He’s dead,” Conrad Racine said.

Most who knew Racine said they felt a deep sense of loss. They mourned a man they knew never meant anyone harm, who lived the way he wanted.

They remember him leaning against the red-brick wall of a house on North Street and drinking Five O’clock Vodka, his favorite brand. His mother would send him gifts and supplies from her home in Claremont, N.H., to Larow’s Market, two doors up the street.

“He was a sweet guy. He had his problems. He’s an alcoholic, but he has a kind heart,” said Kirk Trabant, executive director of the Emergency Food Shelter, where Racine ate most of his meals. “He’s the kind of guy when you saw him you knew everything going to be all right. I really miss him.’

Burlington Police Detective Bill Wolfe characterized Racine as a “nice guy” who drank, got in trouble and was taken to a detoxication center to sober up.

Edith Racine, his 76-year-old mother, said she tried to be the best parent she could, but speculates something happened to him when he was in the Army during the Vietnam War. Racine was honorably discharged from the U.S. Army in 1964.

Mrs. Racine recalled her son declaring when he was a Burlington High School freshman: “I’m not going to school anymore.” He wanted to save his mother the cost of putting him through school. “I told him, ‘you need a diploma,’ ” Mrs. Racine said. He did not graduate.

She said she never lectured her son about his lifestyle, but reminded him that if the people he walked the street with were his friends they wouldn’t give him alcohol.

“Denny lived the way he wanted to live. It wasn’t that he was forced to live that way,” Boucher said. “A lot of homeless people are homeless because they don’t have a choice. Denny had a choice.”

Racine apparently held good paying jobs after he came home from the war. He worked on oil barges in Burlington in the late 1960s and early 1970s and also worked as a landscaping foreman, Mrs. Racine said.

Boucher said that, considering the way Racine lived, she expected him to die anytime. Racine drank 24 hours a day, every single day, she said. He walked the street in intolerably cold weather and would not accept her offers of food or shelter.

Racine’s mood turned ugly toward the end, imagining bugs were crawling all over him, his friends said. He was detoxified at the Chittenden Community Correctional Center on Wednesday, May 31. He was seen at the Food Shelf that Thursday. That same day, the day he died, he showed up at Boucher’s backyard with two men.

“We were all sitting in a corner here and we were having a couple of beers,” Boucher said, recalling the last time she saw Denny alive. “Denny came in here in the yard in a blue car with two guys.”

Boucher said she’d never seen the men before but Racine seemed to know them. They stayed just a few minutes before leaving to go to the Intervale camp.

The camp had always been a good place to return to, especially for Racine.

“It’s quiet. That’s what’s so nice about it; it’s peaceful. It’s away from the city. It’s the only

spot that’s left,” Provost said. Sure, there are drawbacks. Seasonal floods take away their possessions.

And, mosquitoes: “You haven’t seen them … at night,” Martin said. “They’ll chase you clear up the river.”

When two fishermen found Racine’s body seated in an armchair the next day, they said it looked as though he was asleep.

“I hate to see the man go,” Provost said, “but he died the way he wanted to.”