It is a strange process that we put all our heroes and heroines through.

It is a strange process that we put all our heroes and heroines through.

First, we seen them as dangerous and revile them. Then, in death, we (even their former antagonists and adversaries) adopt them and turn them into everything we wished the hero to be, everything we could not make them be when alive.

Much as we turned Martin Luther King, Jr. into a plaster saint that even the racists among us could quote to our own ends, so too shall we render Muhammad Ali.

For Ali, the process actually began when he lighted the Olympic flame at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics.

It was the first time the whole world saw how much Parkinson’s Disease had taken from Ali. Though, an apparition by the time he turned up in Atlanta, he stood tall, powerful and defiant still.

But because he could not really speak for himself, not anymore, people started speaking for him and saying for him things that he might not have said for himself.

His death may complete that process of sainthood. He would be fitted with feet of clay, the better to keep him in place. Writer Dave Zirin is cautioning against that in a Los Angeles Times opinion-editorial.

Kirin wrote:

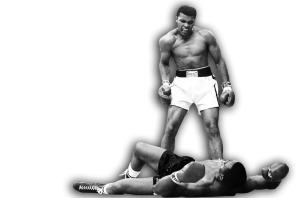

“His life was one of polarization and reconciliation, anger and love, and a ferocious, uncompromising commitment to nonviolence, all delivered through the scandalously dirty vessel of corruption known as boxing. Few have ever walked so confidently and casually from man to myth, and that journey was well earned.”

I’ll quote one more passage but this article is required for anyone who ever cared about Ali and what he stood for:

“Ali’s death, however, should be an opportunity to remember what made him so dangerous in the first place. The best place to start would be to recall the part of him that died decades ago: his voice. No athlete, no politician, no preacher ever had a voice quite like his or used it as effectively as he did. Ali’s voice was playful, lilting, with a rhythm that matched his otherworldly footwork in the boxing ring. It’s a voice that forced you to listen lest you miss a joke, a gibe or a flash of joy.”

In a series of interviews with the BBC’s Michael Parkinson, Ali expanded on his views about everything under the sun. The most iconic of those interviews was the first one, which took place Oct. 17, 1971.

Some of what Ali remarked on then are commonplace today and are taken for granted. But, when Ali spoke, not only did African-Americans lack much power and rights, our society, including the power of our own government, resisted the civil rights movement.