by MICHAEL O. ALLEN, Daily News Staff Writer | Thursday, July 28, 1994

by MICHAEL O. ALLEN, Daily News Staff Writer | Thursday, July 28, 1994

GOMA, Zaire – The heart of darkness lies beneath a smoky volcano.

It starts at the edge of a shimmering lake and stretches across a few miles of flowering bushes and dark rocky plain, proof of Mount Nyiragongo’s periodic tantrums.

It starts at the edge of a shimmering lake and stretches across a few miles of flowering bushes and dark rocky plain, proof of Mount Nyiragongo’s periodic tantrums.

It would be a beautiful reminder of nature’s capacity to uplift, if it were not the epicenter of the Rwandan refugee crisis – a man-made calamity of monumental misery.

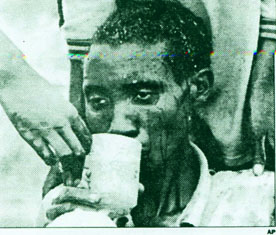

Now it is hell without the fire – a place where children die without pity and men cry without shame.

“It is just so horrible, I can’t explain it,” a relief worker, Noel McDonough, said as he gave a Daily News reporter a lift into the teeming refugee encampments outside outside this border outpost earlier this week.

It was early in the morning, still dark, but light enough to see bodies piled beside the road, dead from hunger or untreated wounds or the cholera epidemic sweeping through Goma with the fury of a Colorado brushfire.

“These people are being wiped out,” he said, “wiped out.”

McDonough had been at the tiny airport helping unload a cargo plane filled with food, medicine, tents and other equipment.

The planes are coming more regularly now–but still too late for at least 20,000 people and probably many more of the 1.2 million Rwandans huddled under the volcano in four major camps and many smaller ones.

As McDonough’s truck nears Camp Kibumba, a powerful odor wafts through the windows, overwhelming the senses, clinging to clothes and skin. It is the smell of the dead and of the dying moaning on the roadside.

As McDonough’s truck nears Camp Kibumba, a powerful odor wafts through the windows, overwhelming the senses, clinging to clothes and skin. It is the smell of the dead and of the dying moaning on the roadside.

Up ahead, as day breaks over the camp, a truck lurches along Avenue Mobutu. Every so often, it stops and two men walking behind it go to the side of the road, pick up contorted bodies and heave them into the back.

The men are wearing bandanas, like Old West bank robbers, and dozens of raggedy children are milling about the death wagons watching the men work–their eyes wide, and afraid.

At one of the camps, a United Nations worker, John Williamson, a child-psychology expert, said many of the children were near death themselves.

“We have to find a hospital for these kids,” he said to Pascal Villeneuve, another UN official. “If not, they die.”

Villeneuve patted Williamson on the shoulder and promised to do what he could, which wouldn’t be much, not with available orphanages and hospitals already choked desperately beyond capacity.

A day in the camps is like the day before, a race against time.

At night, the hungry and the frightened fall to sleep beside little fires to ward off the chill air. Many won’t wake up.

The relief workers crawl into tents and the journalists head back into town to sleep on lawn chairs in front of the dreary Hotel Grand Lace or in a tent city erected by French soldiers just outside the airport.

Hell comes With the usual profiteers and graft economy.

OutSide the tent City, dozens of local Zairian lads crowded around, offering a variety of services. Everything, including a 1-mile taxi ride, costs the same-$20 American.

Inside the airport, a sleepy eyed Zairian immigration official awoke to a wondrous opportunity before him-a Daily News reporter who did not have time to get his Zairian visa and had sneaked into the country.

The official confiscated the reporter’s passport and said the price of getting it back and being allowed out of the country was whatever cash the reporter had in his right pants pocket–about $63 American.

Under the volcano, in the heart of darkness, life was cheap.